Sonali Desai

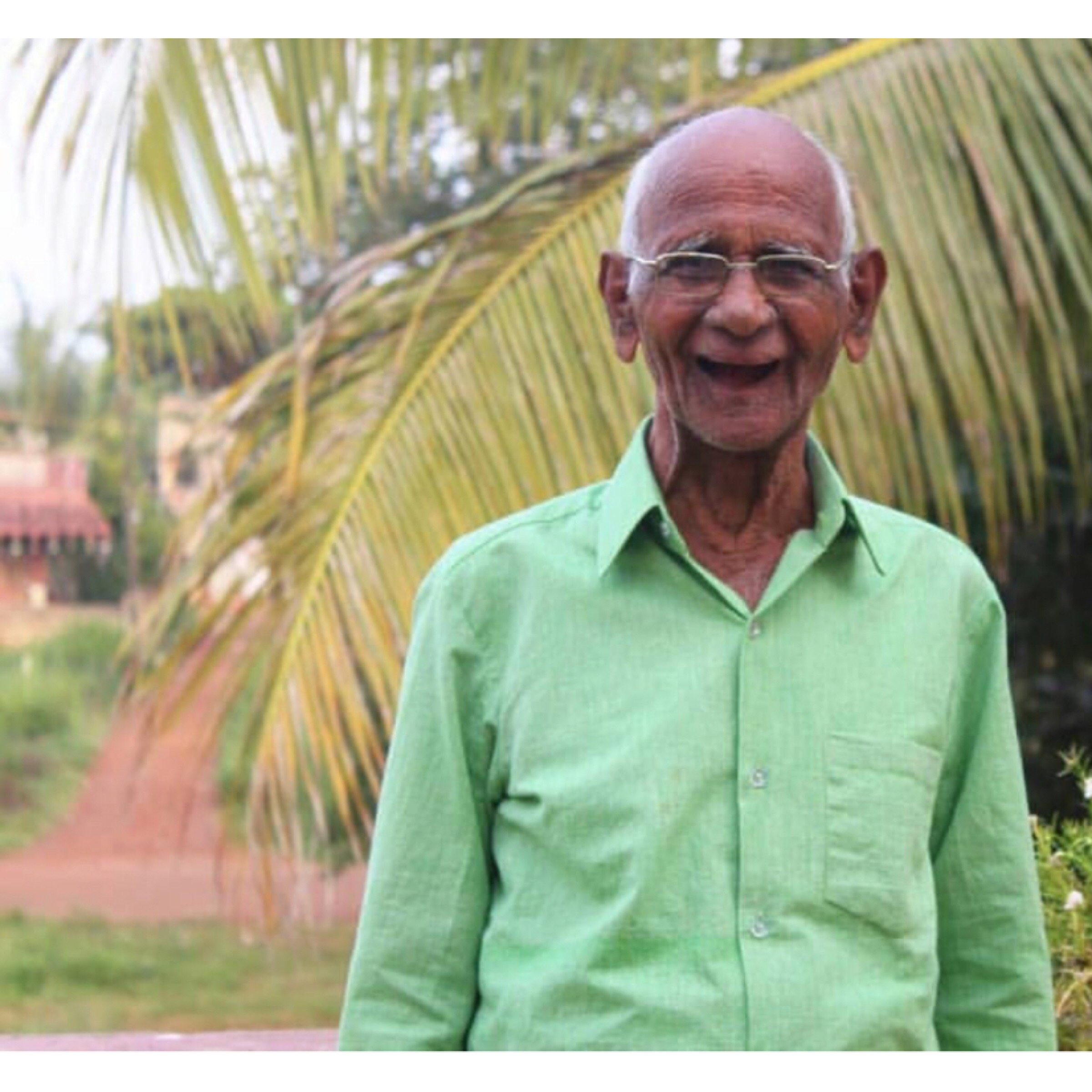

My ajja (grandfather)

Mohan Desai had founded this publication in 1956, shortly after state boundaries were reorganised on linguistic lines. While the Belgaum region

became a part of Karnataka, Maharashtra also laid claim to the territory. It

still does. It was in such a charged socio-political milieu that this

publication had taken off. Back then, it used to be a weekly and was called Darshan. The paper became a daily in

1963 and got rechristened as Lokadarshan.

I vividly remember how ajja

had described the struggles in starting this Kannada paper in what's deemed

a disputed territory. Contentment and a quiet grit were writ large on his face

as he looked into the distance and said: “I had only five rupees in my pocket.

If people hadn't believed in me, I couldn’t have built Lokadarshan. When I had first set up the printing unit, it was set

ablaze by some people. But I never gave up.”

It wasn't necessarily that the Marathi-speaking members of

the region had taken umbrage at the launch of a Kannada publication. For, my ajja's kith and kin too were among his detractors and disruptors. Decades

have passed but the Belgaum issue remains a hot topic and still evokes passion

on both sides of the border. Why, there are politicians whose entire career has

this very discontent to thank for. Such is the leverage that this topic

possesses, yet ajja never sought to

capitalise on it.

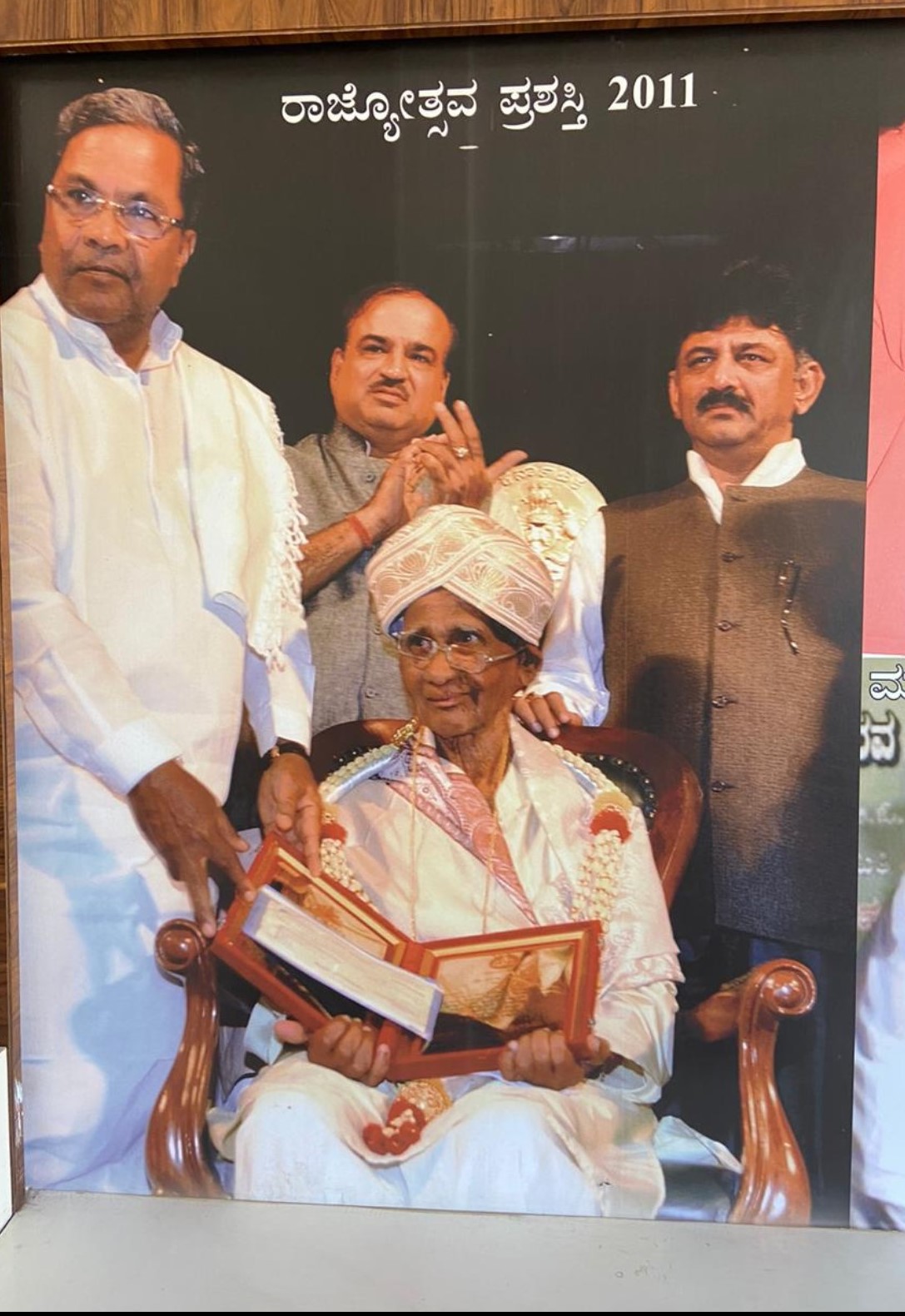

For him, fairness of news and ethics of journalism alone were supreme causes. Through Lokadarshan, he espoused unbiased political reporting and secularism. Be it editorial duties such as reporting and editing, marketing obligations such as advertising and circulation or even printing, he paid great attention to details. He was thorough and meticulous in every sphere of operation involving this newspaper. Excellence in journalism and his commitment to starting a Kannada newspaper in Belgaum—the first in the region—won him three state honours, including Karnataka's highest civilian honour, the Rajyotsava award.

One of the most remarkable aspects of his persona was his

zest for life: he used to tell us that he’d live for a hundred years. On his

95th birthday, when I had asked him if he had any more wishes to be fulfilled,

with moist yet twinkling his eyes, he quickly replied, “I have another idea for

business. I want to do this... that... And…”

We were asking about wishes whereas this man was all about

dreams. Big dreams!

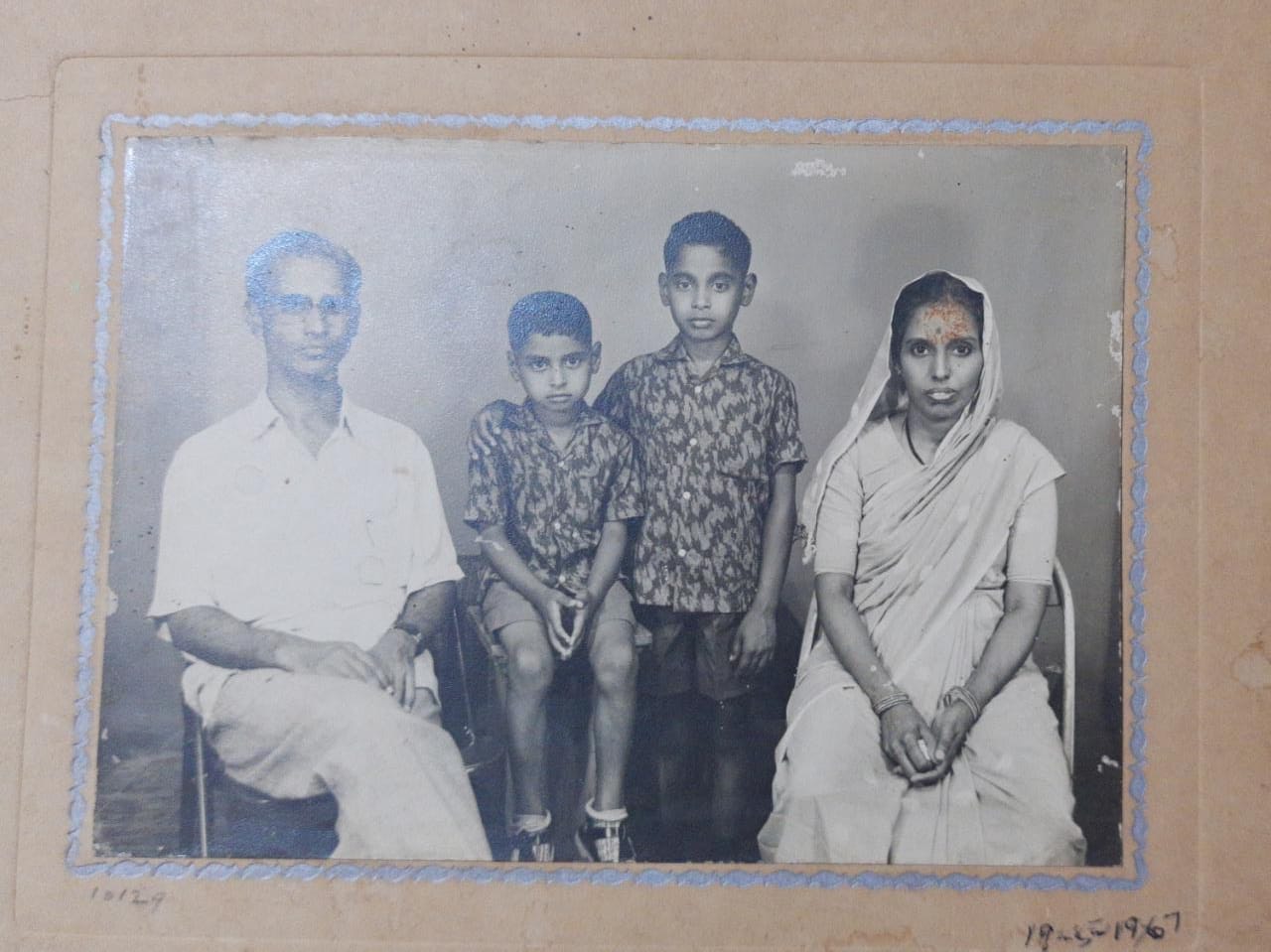

While recalling his life, it's imperative to recall its

foundation: my late ajji Sheela

Desai. My grandparents are testimony to the adage that there is a woman behind

every successful man. The idea of starting a Kannada newspaper in northern

Karnataka was hers. Their love story is one of a kind. In the 1940s, my

grandmother had graduated and worked with the British government before

starting a career in an NGO as a social welfare officer in Hudali village. This

is where she met my grandfather and proposed to him for marriage. (Now I know,

hers is the gene responsible for the braveness of the girls in our family.) At

that time, my ajja had left his home

to take part in the freedom struggle. He had no money and little education. My ajji funded his graduation and sent him

money via post until they got married. After marriage, she got busy with kids

and ajja fulfilled her dream of

running a newspaper.

He had turned 97 this year but not once did he use a cane to

walk around, not even a helping hand. While he had the option of having food

served in his bed, he always chose to climb up one floor to eat his meals on

his wooden, regal eight-seater dining table, which he had tastefully designed.

He didn’t even have the common ailments of old age, such as low blood pressure

or diabetes. He was ageing gracefully.

We knew he had to leave us one day. As the end of life

approaches for a loved one, the kindest thing you can do is letting go. He left

us shortly before the mango season—his favourite—could arrive. Leaving behind a

bunch of loving and inspiring memories, he now rests in peace under a mango

tree.